Complexity 101 and the P-NP question

Anyone working with computer algorithms sometimes has to reflect on the question what the complexity of that algorithm is. Last week I tortured my poor laptop by letting it crunch away the whole night on a planning problem using A* with the $h_{max}$ heuristic, only to find that upon waking up 1) the cpu heat was quite critical and 2) that the search space exploded and the program did not terminate. In situations like this is nice to have an estimate about whether it even makes sense to wait for termination (and no it did not, the $h_{max}$ heuristic performed very poorly).

In such a scenario it is wise to do a complexity analysis of your algorithm: given a particular input size, how much space and time is required to provide the wanted output? Usually people do not go looking for a stopwatch in some dusty drawer, but are interested in the general order of complexity; it has to be “in the ballpark.” In some cases, algorithms can be plain bad: their complexity is due to bad design.

But a more fundamental issue is when a problem is simply so hard that we are not even sure an algorithm exists that can solve it efficiently. Therefore it is not only useful to discuss the complexity of algorithms, but also the hardness of problems. In this post, I want to introduce the basic concepts expressing the hardness of such problems. On top of that, these concepts will be helpful to understand one of the seven “Millenium problems”, the solving of which is rewarded with one million dollar: is the set P equal to the set NP? Read on…

Big-O-Oh ¶

The order of complexity can be assessed in the so-called Big-O notation. It follows two simple principles:

1 - The main bottleneck for any algorithm is the most costly component of that algorithm.

2 - We do not care about the exact number of computations done, but about the relation the input size has to the required amount of space and time.

So let’s assume we have some input with size n to feed our algorithm, which requires a certain amount of time and space to process. And now assume that the input becomes twice as big. Does that mean that we also need twice as much space and time to get the algorithm to output what we want? In that case, there is a linear relation between the input size and the space or time complexity, which is denoted as O(n). If we make the input size twice as big, and it turns out that the required space or time is four times as large, then we are dealing with a quadratic relation instead, which can be expressed as O($n^2$). This illustrates bullet point 2.

To illustrate point 1, let’s build forth on the same example. If we have some algorithm that combines multiple operations, of which one is linear (O(n)) and one is quadratic (O($n^2$)), then the complexity of the algorithm is dominated by the highest-order relation, which is quadratic in this case. So in this case, we still speak of O($n^2$).

In general, we speak of polynomial time algorithms if we have, for input size n and some constant exponent c, O($n^c$). For c=1,2,3 respectively, we speak of linear, quadratic and cubic running times. Having an algorithm run in cubic time is pretty bad, but at least we can make a pretty good assessment about its feasibility in practice.

But then there are the true monstrosities of complexity: exponential time algorithms that are exponential in input size: O($c^n$), where c > 1.

Problems for which no polynomial time algorithm exists are considered to be intractable, where intractability means there exists no efficient (i.e. in polynomial time) algorithm to solve them.

Decision problems ¶

Our main question concerned the hardness of problems. The most basic question we can ask here is whether any given problem can be solved. A second question is how hard it is to verify that a solution is correct, if someone were to come to us with a proposed solution.

Let’s say we have the following situation: we have a graph with weighted connections, and some start S and some goal G. Now our problem is that we want to find the cheapest path from S to G. We could of course go ahead and simply try to solve it. But let’s say that this unfortunately does not work out… You are scratching your head and then ask: did I not find an efficient algorithm for solving my problem, or does such an algorithm not exist?

In other words, you would want a systematic approach for deciding whether a problem is solvable. In this case you would need to ask: does there exist a path such that the path cost is at most k? Significantly, this question is answered either by yes or no, and does not yield a solution (a shortest path). This is called a decision problem. But although this type of problem does not provide us with a solution to our original search problem, it does indicate is how hard the corresponding problem is to solve!

Classes P and NP ¶

Given these decision problems that indicate the hardness of the corresponding search or optimization problem, we can distinguish complexity classes:

Definition of the class P ¶

P is the class of decision problems that are solvable in polynomial time, i.e. there exists an algorithm with worst case time complexity of O($i^c$) that can decide for every i $\in$ I whether D(i)=yes or D(i)=no.

Definition of NP ¶

NP is the class of decision problems D for which yes instances (D($i_{yes}$)) are **verifiable** in polynomial time.

In other words, if someone where to come to you with a solution to your problem, how hard is it for you to verify that this solution is indeed correct? This definition of NP is slightly tricky, because it is only defined on “yes-instances”, i.e. a solution that claims to be correct.

Take a graph 3-colourability problem, taken from a lecture I followed on complexity. This means that we have some graph, and we ask whether we can colour the nodes of the graph with only three colours in such a way that none of the same coloured nodes are directly connected to each other. So the decision problem at hand here is: is there a colouring of this graph such that none of the vertices sharing an edge have the same colour?

Example ¶

1 - Finding (“deciding”) such a colouring is hard, and cannot be guaranteed to be doable in polynomial time.

2 - Given a colouring, it is easy to verify that it is correct.

3 - Given a wrong colouring (a no-instance), it is hard to determine if the graph is not 3-colourable in general, or if the current colouring just happens to be wrong.

The third point illustrates why NP is defined on yes-instances of the decision problem, because verifying yes instances is not the same as verifying no-instances.

Relations between P and NP ¶

The P-NP question concerns the exact relationship between the sets P and NP. In other words, if we know a problem is decidable, what does that say about its verifiability? And if a problem is verifiable, what does that imply about its decidability?

One thing is clear at least: P is a strict subset of NP. If a problem is decidable, it must also be verifiable. Consider this: if you need to verify a problem and it is in P as well, then it is always possible to throw away the solution that has to be verified and instead find it yourself, all still in polynomial time.

However, whether NP is also a strict subset of P is exactly the million-dollar question. In other words, does P=NP hold?

If there exists a proof of membership in NP (verifiable in polynomial time) but simultaneously a proof of non-membership in P (there is a super-polynomial lower bound), then we have shown that NP is not a strict subset of P and that P $\neq$ NP.

NP-hard ¶

It has so far not been possible to find a problem that is in NP but not in P (so again, a very hard problem that we can verify but not decide in polynomial time). However, it is possible for any NP-problem to decide if it is amongst the hardest problems in NP, more specifically at least as hard as all other NP problems.

This is a meaningful insight, because if we find for a given NP-hard problem that it also belongs to P, then we have shown that all NP problems belong to P, effectively proving P = NP. Intuitively, this makes sense: if we can find a P algorithm for the hardest problem in NP, then we must also be able to do that for the easier problems in NP, given that they can be rephrased in terms of the harder decision problem.

Conversely, since we do have the intuition that P $\neq$ NP, proving membership of NP-hard is a good indication (not proof!) that the problem is verifiable but does not have a polynomial time algorithm for deciding it (P membership).

All or nothing! ¶

To recap shortly: there are some problems that we can verify quite easily in polynomial time, but for which we do not have a polynomial time algorithm for actually finding a solution. An example was the graph 3-colouring problem. We ask ourselves: do we not have an algorithm for deciding that problem because we simply have not found it yet (so possibly P=NP), or because the problem is so hard that there simply cannot be any efficient algorithms (P$\neq$NP)?

We have also considered that proving that a P algorithm exists is doable by actually providing such an algorithm, while proving that it does not exist is extremely hard. What could be a tactic?

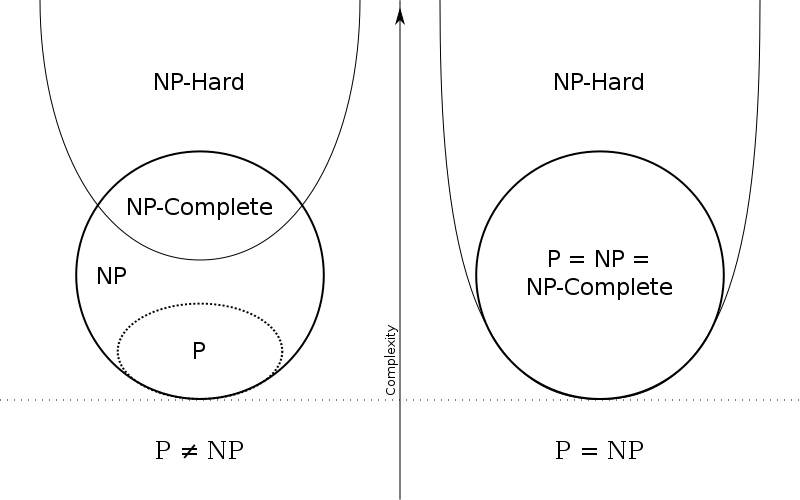

Consider the following figure, taken from wikipedia:

Diagram of P and NP under two different assumptions

Just for completeness: from the illustration you can see that NP-complete is the class of problems that are both in NP and in NP-hard.

Let’s say that we suspect that there is no polynomial time algorithm for a given problem. And let’s assume I have some problem in NP of which I already know that no polynomial time algorithm exists for deciding it. If we could somehow show that this problem without efficient solution can be reduced to the problem we are considering, then we also know that the problem under consideration is not in P.

If we keep on reducing problems like this, we end up with an all or nothing issue: once we can show for one of those problems that it is not in P, then we can show it for all problems in NP that were reduced from it. Conversely, if we find that one of the NP-hard problems, to which all other NP problems can be reduced, is in P, then we have shown it for all problems in NP. To understand why, we have to carefully look at what this reduction precisely means.

What can we conclude from a reduction? ¶

In order to preform a reduction, we need to find an algorithm that translates every instance of decision problem $D_1$ to an instance of $D_2$ such that every yes-instance still is a yes-instance, and every no-instance is still a no-instance in the other decision problem. In particular, for the above reasoning to hold we need these reductions to be possible in polynomial time.

Assume we reduce $D_1$ to $D_2$. Then every found solution to $D_2$ in polynomial time can be translated back in polynomial time to the original domain, meaning that also in that domain there must be a polynomial time algorithm.

The notation $D_1$ $\leq$ $D_2$ means that $D_1$ is reducible in polynomial time to $D_2$ (The notation is incomplete but suffices for now). We could read the smaller or equal sign also more informally as: $D_2$ is equally hard or harder than $D_1$ .

We have $D_1$ $\leq$ $D_2$. Two conclusions are possible:

1 - If $D_2$ can be decided in polynomial time, then so can $D_1$, since $D_2$ is at least as hard.

2 - If $D_1$ cannot be decided in polynomial time, then $D_2$ also cannot (since $D_2$ is at least as hard, and has the exact same solutions due to the possible reduction).

In fact, the second statement follows logically from the first: let D1 mean that $D_1$ is solvable in polynomial time and let D2 mean that $D_2$ is solvable in polynomial time. Then D2 -> D1 is equivalent to ~D1 -> ~D2 (contraposition).

If the above reduction holds, we can not conclude that if $D_1$ can be decided in polynomial time, that $D_2$ also can. The reduction only works in one direction. It shows that any solution to $D_2$ must also be a solution to $D_1$. So let’s say we find a solution for $D_1$… Then we cannot say anything about a solution to $D_2$. This is also intuitive, since $D_2$ can be way harder! A solution would of course be to show that the reduction is symmetrical.

So this is the crux: if we are able to reduce all NP problems to a set of the hardest problems in NP, i.e. NP-hard (and NP-hard problems can be reduced to each other), that means that if we find a P-time algorithm for deciding a NP-hard problem, we have one for all NP-hard problems, since there are shown to be polynomial time reductions to the NP-hard problems. Quite a mouth full!

But how to show membership to NP-hard? ¶

It is very hard though to show membership of NP-hard because you need to show that all decision problems in NP are reducible to the problem in NP-hard. The first problem proven to be NP-hard is the CNF-Sat problem: for any logical formula in propositional logic, is there a way to make it true?

From there on the burden of proof is a bit lighter for proving problems to be NP-hard. We do not have to reduce every problem in NP to our problem of interest anymore. Now we “only” have to show that a problem is at least as hard as the CNF-Sat problem. In other words, we have to reduce from CNF-Sat to our problem of interest (not the other way around!). That guarantees that our problem of interest is indeed at least as hard as any other problem in NP. In general, once we have other NP-hard (more specifically, NP-complete) problems, the tactic is to reduce from any NP-hard problem to the problem of which we try to prove NP-hardness.

The 1M$ Question ¶

To conclude, two potential tactics for deciding this question are:

- For P=NP. Show for a NP-hard problem that there is a polynomial-time decision possible. Since that NP-hard problem is at least as hard as any other problem in NP, we have effectively proven P=NP.

- For P$\neq$NP. Somehow show that there is a problem for which a polynomial-time decision is not possible, but that is verifiable. In other words, that it is in NP but not in P (This is the only option, since P definitely is a strict subset of NP).

Credits: This post contains my proceedings from a lecture given by Johan Kwisthout, attended at the Radboud University Nijmegen.