Security and privacy: some key concepts

Discussions about privacy- and security issues are in the news daily, related to some scandal, data leaks, new regulations (GDPR), increased surveillance in response to terrorism, etc. But what do these concepts of privacy and security actually mean, and how do they relate to each other? Everyone probably has some intuitive notion of these concepts, but on a closer look, they are more complex than one would expect. Discussions about privacy and security should begin with: what privacy, what security? These questions, despite their perhaps “dry” conceptual nature, are important for anyone interested in what is at stake in the privacy- and security-related discussions going on right now. In fact it is also important for those that do not share this interest, because the results of these discussions will affect them nevertheless. The goal of this blog post is to provide some pointers, distinctions, and questions; not answers. I have only relatively recently begun to engage with these topics myself and by writing this post I hope to test and develop my current understanding of the topic, which is very much in progress, perhaps even infantile.

Security and privacy ¶

A first distinction need to be made between “security” and “privacy”. Security relates to the regulation of access to some system. In a digital context these would be computer systems, from the servers of a secret agency to the personal computer of your grandma, if she has one. This is not the same as privacy, which can mean many things but in general essentially relates to persons or individuals. So a first basic distinction perhaps is that digital security pertains to various aspects of a communication channel itself, whereas privacy relates to the individuals involved in this communicative process, mediated by some technology.

Nevertheless security is a relevant topic for privacy. For a significant part, the security of communication between persons is a precondition for guaranteeing privacy. But it surely is not a sufficient condition. For example, with good cryptography one can make sure that third parties do not read the content of your communications. But the very fact of your communication may contain information that intrudes your privacy, e.g. it contains information about who you know, or about your location (e.g. where you work or live); which is information that you perhaps did not intend to share and which might be very sensitive. In that sense, cryptography, or computer security in general, solves problems only by moving them to another domain.

In some discussions security and privacy seem to exclude each other. Acts of terrorism never fail to spark debate on whether to give surveillance agencies more power to snoop on civilians, i.e. reduce their privacy, under the banner of increasing security against people with malicious intent. In that sense, the question becomes: security or privacy? But what we need is security and privacy.

In the following I want to map out some useful concepts related to security and privacy that I encountered so far when reading on this topic.

Security ¶

Considered naively, computer security can be easily thought of as some monolith stating “here and no further”. But in reality, security is a fluid concept that should be understood relative to an attacker with a given amount of resources. At the border case, absolute security requires resistance against an attacker with infinite resources. The notion of such an “absolute” security is meaningless, as it arguably requires a complete blockage of access. However, the point of securing real systems is not to block access as such, but to regulate access to whatever assets or capabilities that system has. That is, it needs to allow access, but only to the right people.

So the concept of security only makes sense against the backdrop of a potential attacker. But on top of that, whether something can be called secure depends on the context of the system, its purpose and the needs of its users. The security goals of various systems might differ, and the way in which we call system A secure can be different from the way we call system B secure. Let’s look at some examples of different security goals in different contexts. In order for critical systems in hospitals to be secure, their availability needs to be guaranteed at all times. If in that same hospital medical information is stored about you, its confidentiality is strictly required. Now imagine you need a blood transfusion, but someone changed the information on your blood type in the medical system, i.e. its integrity has been breached, with potential lethal consequences. In another example, to reliably transfer money using online banking, confidentiality is less of an issue than the authenticity of the sender, bank, and recipient. E.g. when you transfer money to the bank you want to be sure you do not in fact transfer money to a criminal “man in the middle”. More easily overlooked is the principle of non-repudiation: after you have transferred your money, you cannot later deny you did so.

You can think of many contexts where one security goal is absolutely required, whereas another may be less relevant. In other words, in different contexts “security” means different things, depending on the relative importance of the aforementioned security goals: confidentiality, integrity, authenticity, non-repudiation, availability. The goal of this section was merely to transmit the basic intuition that the concept of security is less univocal than it may seem, and provide some first differentiations.

Privacy ¶

But even if the communication is secure, what information do you give to these systems? How are they stored, and how are they used? Do you keep any control over this? Imagine the aforementioned hospital leaking your medical information to your health insurance: you can bet your fees to go up. A hospital doing so would be an extreme case. But now imagine a free fitness app doing the same after storing information about your health and condition (e.g. hearth rates during running, or weight etc.). The people installing that fitness app, after accepting the “terms and conditions” that they quite reasonably did not read, might potentially sell their data for such usage without being aware of it. So although that app would be “free” in the sense of gratis, it does come at a cost.

Privacy as a concept seems tightly entwined with the idea of an individual. The above example concerns sensitive information about individuals, and indeed most discussions about privacy nowadays concern the use of personal data by various companies and the control individuals keep over that use. This sense of privacy can be traced back to Westin’s definition of privacy in 1967 as “the claim of individuals […] to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others.” Privacy in these contemporary discussions thus means something like “control over your data”, and is a unique issue that occurs in the digital era. It is interesting that most people would probably not bother to hide their shopping cart when doing groceries, whereas knowledge of your online shopping behavior more quickly becomes a privacy issue. Privacy can thus mean something different online and offline. Simultaneously, the integration of digital devices into our lives increasingly blurs the line between online and offline, and also between public and private.

Perhaps this difference has something to do with a perceived sense of anonymity you have when sitting at home browsing the internet. In the domestic sphere of the house, you act from within a relatively protected and secluded situation, which suggests privacy in the “old fashioned” sense of “being left alone” (as defined by Warren and Brandeis already in 1890).

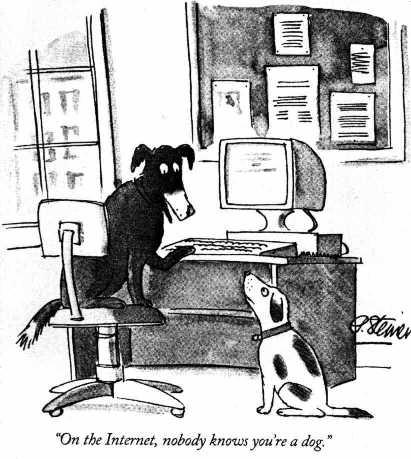

This situation shows a clear incongruency between different conceptions of privacy: you are indeed left alone, but simultaneously you are not in full control of your own personal data, and moreover this data is used to manipulate you without you realizing it, for example in the results you see for internet searches (cf. the “filter bubble”), or in targeted advertising. You do not only lose control over the information you expose to the internet, but also lose control over what information is shown to you. Perhaps the net is neutral, but the information you “find” (or: is presented to you), certainly is not. The famous meme “on the internet, no one knows you’re a dog”, was valid years back, but over time changed into the description of a comfortable illusion.

It depends on your definition of privacy whether it is violated or not in the scenario I just sketched. But most interestingly, what it shows is that the digital era effectively initiated a transformation in the concept of privacy that is occurring as we speak. A digital-savvy portion of the population is constantly sounding alarms left and right about privacy issues, whereas others do not only not experience a breach of privacy, but also think the discussion is nonsensical because they “have nothing to hide”.

On the way to privacy… ¶

These initial considerations barely scratch the surface. I want to think more about privacy in the coming months in all its nuance and complications. For example, what is the relationship between privacy and intimacy both in the “analogue” and digital domain? What are the links between related concepts such as secrecy or confidentiality, which are all partly overlapping but not the same? How does privacy relate to an individual’s freedom? It is also possible to develop perspectives that rely less on the individual, as I did here. How does privacy take shape in negotiations between individuals in communities, i.e. how is privacy also essentially a social process? And how can such a multi-faceted dynamic concept be adequately represented in law, which seems primarily concerned with regulating data processes?

A philosophical discussion that takes a step back before being activistic is relevant, because how can we really guarantee privacy in the applications we implement, or protect it by law, without having a clear view of what it is? That is not a plea for passivity, as it is unreasonable to expect of anything worthwhile that it can be captured in a few clear concepts. Neither does it invalidate raising your voice before being completely informed, because a certain degree of “conceptual entropy” (trying out a new term here) is unavoidable in a debate that is very much alive and in progress. Instead, I would say that conceptual reflections can contribute to informed action, which in my opinion always includes expressions of doubt rather than offering false certainties. A bit of reflection is needed to be a successful user of the internet, consciously shaping our pluralistic digital identities in all the systems we interact with, rather then becoming its victim.